Ceramics, Page 1

Home

Back to Antiques page

Forward to Ceramics Page 2

Meissen Coffee or Tea Pot, Germany, 1728.

Purchased from Hart-Adams Antiques. For centuries, the Chinese held the closely-guarded secret to the manufacture of hard-paste porcelain, famed for its translucent beauty and durability over the softer pottery found in the rest of the world. The German firm at Meissen was the first in Europe to figure it out. With royal support, they brought in the best painters and gilders, and during the first half of the 18th century made some of the finest porcelain objects that remain highly collectible. This pot was from the series of Italian harbor scenes painted by Christian Friedrich Herold, and is in exceptional condition. A virtually identical one is in Hampton Court Palace, London.

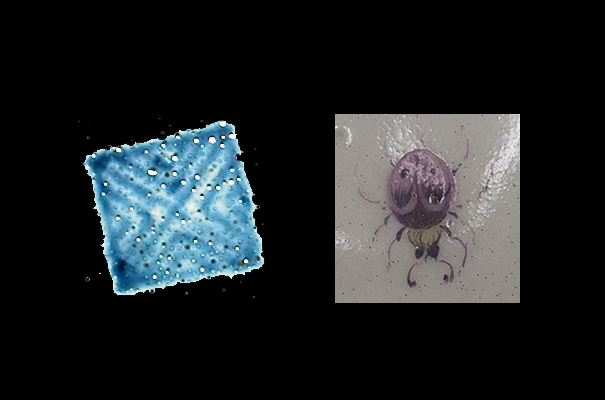

The Meissen factory hallmark in underglaze blue and the gilder's mark.

Toby Jug, England, Neale & Co., 1790-1800

Purchased from Wynn Sayman. Toby jugs can be used for drinking, but a new trend had arisen throughout Europe: items were made to go into the middle-class house as decorations and not purely for function. The earliest Tobys had a running underglaze. Neale was one of the first and best to use enamels. Our Toby has the ruddy drinker's face and pox (syphilis) marks meant to ridicule those who led a wilder lifestyle. These jugs continue to be made over 200 years later, and are available in many styles.

Bellarmine Jug, Frechen, Germany, 17th century

These jugs were widely used in northern and western Europe for transporting beer and wine during the 17th century.

The mask is said to be a grotesque caricature of Cardinal Bellarmino, who was hated outside the Catholic church. Bellarmino tried to outlaw alcoholic beverages throughout Europe, and his face ended up on the bottles in satirical protest. A brutal inquisitor who persecuted many, he is most famous for writing the letter summoning Galileo to Rome to redact his support for the Copernican heliocentric system.

Below the mask is a city seal which we have not been able to identify. 11" tall.

Westerwald mug, Germany for the English market, 18th century

The English public had a cause for major concern: they were being cheated out of a full pint at many pubs. So the measure became law, and mugs with the royal seal became a standard. This particular mug was from the early period. Later ones were more simply or crudely ornamented. 6" tall.

Sevres cup and saucer, France, 1761.

Purchased from Hart-Adams. The early Sevres production was the finest soft-paste porcelain ever made. It has a look and feel that have never been reproduced, and the quality of painting and gilding were the best. This manufactory was supported by the King of France, and employed the best craftsmen and artists. The Sevres double-L hallmark was begun in 1751, and letters were added to denote the year of manufacture starting in 1753. The letter "I" on the bottoms of the cup and saucer indicates they were made in 1761.

Worcester cup, c. 1770

The Worcester factory figured out the porcelain formula, and began to produce wares in a great variety. The scale-blue ground and birds were meant to emulate the Sevres seen above. The minerals they used fused into a characteristic greenish tint that must be learned if the collector wants to avoid the many hard-paste fakes out there.

The underglaze blue hallmark under the cup was one of several used by Worcester. This little bug would have been a surprise at the bottom of the cup when the tea was finished. Insects were often used to cover small flaws in the porcelain. Bugs will not go away, and continue to be present in manufacturing and software.

Coalport part service, England, c. 1820

Painting probably by Thomas Brentnall, who was formerly a flower painter at Derby.

Impressed mark on reverse of plates.

Pair of serving dishes possibly also by Coalport